Harvey's

"From oysters to eggs, one black lawyer's quest to dine out in D.C," John Kelly's column in this morning's Washington Post t is about the day when Emanuel Molyneaux Hewlett went to a famous Washington eatery to get some oysters.

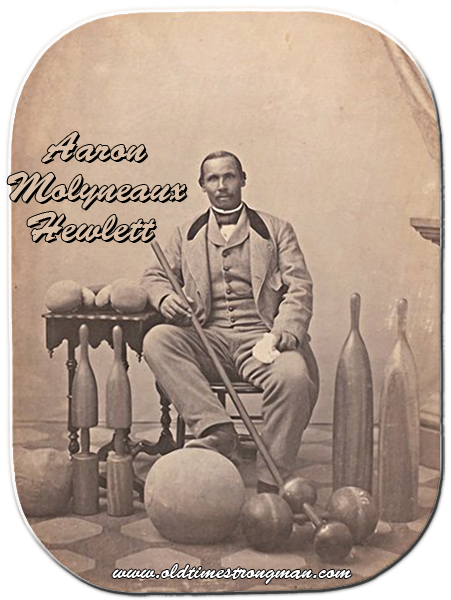

Hewlett was a rather prominent man at that time. He had grown up in Boston where his father, Aaron M. Hewlett, was the first African American instructor at Harvard University. He oversaw the state of the art gymnasium there. Emanuel Molyneaux Hewlett was the first black graduate of the Boston University School of law; he had a thriving legal practice in DC. Kelly writes that Hewlett was "a leading citizen in Uniontown, as Anacostia was called then and his sister Virginia was married to Frederick Douglass's son." Later in his career Hewlett was a justice of the peace and a judge in Municipal Court in DC and worked on ten cases that went to the U.S. Supreme Court.

So he was well known and well behaved and you'd think he would be able to get a meal in a restaurant. But the date was December 5, 1887. On that day Hewlett and his similarly distinguished African American guest were told they couldn't eat at Harvey's. They were asked to leave. Kelly tells the story. "Hewlett filed a complaint against Harvey's, claiming it had violated the Equal Services Acts of 1872 and 1873, which forbade racial discrimination in D.C. restaurants." The restaurant was fined $100.

There it might have ended -- but Harvey's decided to appeal on the grounds that, while the law obliged them to serve any "well-behaved and respectable person," Hewlett was NOT well behaved. "The defense attorney produced a story from the Washington Evening Star newspaper recounting a trip Hewlett had taken two months earlier to French's, a lunch room in the Center Market...Hewlett had ordered three eggs, a cup of coffee and some biscuits, for which he was charged three times what the meal should have cost. He asked for the price list...and was told there was none." When he tried to leave, Hewlett found the doors locked. The black attorney had to climb out a window, then walk along a balcony before entering another room that had access to an elevator. This proved, Mr. Harvey testified, that Hewlett was a known check skipper. Knowing that, what restaurant would serve him?"

A jury (from which the lone black member had been stricken) deadlocked and the case was ultimately dropped by the prosecution. The Evening Star editorialized that "the inexorable Hewlett will not relent" and went on to ask -- if restaurants are to be integrated, what is next? Mixed Schools? Kelly quotes the editorial. "The Star believes that the mass of our colored people favor separate schools."

It really is useful to be reminded how entrenched racial segregation was and how widespread were the painfully condescending attitudes that supported it.

I actually remember eating at Harvey's restaurant with my mother sometime in the 1960s. We had she crab soup and it was delicious. I was impressed by the white tablecloths and excellent service. Now I wonder -- were they serving African American customers then? It is a question it would never have occurred to me then to ask. I am grateful to John Kelly for writing up this story.